Walling off third-party cookies: Tech giants take on the privacy challenge

- Thursday, May 23rd, 2019

- Share this article:

Teavaro’s Nico Pizzolato discusses how Google and Facebook’s proposed privacy tools may accelerate the end of the third-party cookie for digital marketers, continuing a trend that started with GDPR, ad blockers and browser restrictions.

When a few months ago Apple turned the screw on third-party cookies, banning them from Safari, improvident marketers tried to figure out ways to get around the problem and fill out the blanks in customer identification, hunting for short-term fixes. Those who have a more heedful approach know that this is part of a larger trend and needs a more robust solution.

When a few months ago Apple turned the screw on third-party cookies, banning them from Safari, improvident marketers tried to figure out ways to get around the problem and fill out the blanks in customer identification, hunting for short-term fixes. Those who have a more heedful approach know that this is part of a larger trend and needs a more robust solution.

Since GDPR and the resonance of stories such as Cambridge Analytica, pressure has been mounting on tech giants such as Google and Facebook to protect more of their customer privacy from third-party intrusion, or at least give them the instruments to do so. Google announced its own forthcoming anti-tracking update for Chrome earlier this month, closely mirroring Safari’s ITP 2.2, but giving users the option to deploy the feature (which is not the case for Safari). Little more than a week passed and Facebook — lately the ‘bad guy’ of privacy — has announced its own ‘clear history’ tool that makes users’ off-platform data anonymous to advertisers. Contrary to Apple, ad revenue is the bottom line for Google and Facebook, so what does it all mean? And what is the impact to marketers who have been relying on the capabilities catalysed by third-party cookies?

First of all, it must be stated that, to date, we have only announcements to work from. We don’t know exactly how these tools will look or function, and we don’t know how strongly they will be pushed to users. Usability will be crucial to uptake as stronger consumer awareness of privacy coexists with the normal logics of user experience, which demands that any privacy protection be few clicks away. In other words, Google’s update might not be the avalanche ploughing into ad targeting that it may superficially appear to be.

While Safari covered a tiny percentage of the browser population, at least on desktop (the story on mobile has been quite different), Chrome is the market leader, with around 60 per cent of the market for both desktop and mobile browser use. A moderate uptake from users to block tracking might have significant impact on the ability to target audiences through third-party data. Google might stand to benefit from this, and not just in the superficial PR win. Though in the fanfare surrounding the announcement, the company has striven to come across as a stalwart of transparency standards, ‘empower[ing] users to make informed decisions about how to control the use of their data’, Google’s own ad-driven model will be largely unaffected, even boosted by its loss of competitors. Computer scientist Jonathan Mayer dismissed the move by saying that, ‘this is not privacy leadership — it’s privacy theatre’. If anything, Google might have envisaged that marketers would need to turn more towards its ‘walled garden’ of identified users to reach their audience. Others have maligned that Google’s anti-tracking update would end up gnawing at Amazon’s ad revenue, as the latter, like any publisher, would find it difficult to reach audiences away from its own site.

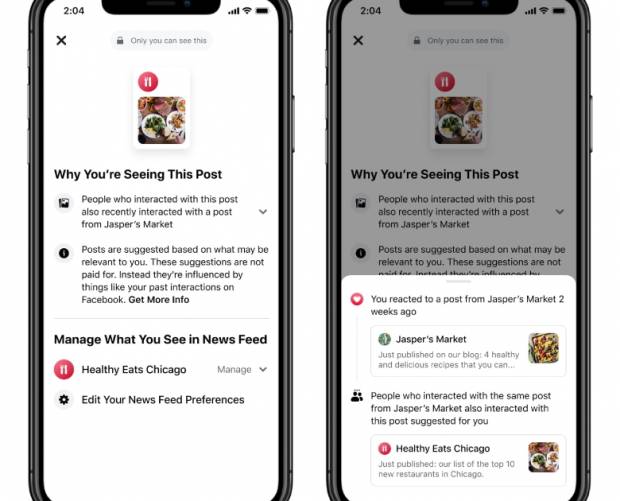

At the moment, we know even less about Facebook’s ‘Clear History’. Regulators have long-awaited a firm move from Zuckerberg against the reach of third parties to its billions of users, but the answers have come sporadically, in bits and pieces. At Facebook, the crisis has been more profound for the implication on electoral politics that followed Cambridge Analytica, so it’s not only about business anymore. ‘Clear History’, which will be made available in the second half of the year, promises to make users’ data anonymous off Facebook’s platforms, which means that it cannot be used for targeting. The company states that, “This means that targeting options powered by Facebooks business tools, such as the Facebook Pixel, cant be used to reach back to someone with ads. This includes Custom Audiences built from visitors to websites or apps.” Facebook will still store the data, but it will use it only at aggregate level, for analytics. In other words, brands that have been accustomed to retarget users who have first visited their site and then moved on to Facebook will lose the opportunity to do so, making them more reliant on Facebook’s advertising offerings – at additional cost – to make up that marketing shortfall. Again, if the user activates that feature.

It’s a big if and, as in the case of Google, we don’t know how strongly will Facebook care for educating the user or whether it will be user-friendly. For instance, it might show a long, tedious list of apps and websites that use Facebook Pixel, SDK and API and which looks like the ones we get now from companies that want a minimal GDPR compliance. In any case, the mantra is the same: give more control to users. For Facebook, “it improves the way they feel about ads and the businesses they interact with online”. And Zuckerberg walks the talk, or so it seems, by having initiated and funded TTC Labs, which has brought many stakeholders together to design privacy-friendly prototypes.

On the face of it, both Google and Facebook’s proposals are aimed at providing much needed responses to data privacy concerns having lagged behind the likes of Apple. But it is no secret that these “walled gardens”, unlike Apple, generate their revenue from digital advertising. As such, when analysed, these changes could help both increase their already overwhelming grip on the market; Google, for one, have been canvassing other players in the marketing ecosystem for years before developing this. With such evidence, it is hard to believe that these are reactionary responses to oversights ahead of carefully planned moves. Google and Facebook are embracing the inevitable end of the third-party cookie. This should be seen as an acknowledgement from the fortresses of big data hubris that the relationship between the data subject and the data controller is shifting. Privacy is driving innovation in a changing digital marketing landscape; marketers should address these new challenges before the walls become too high to scale.